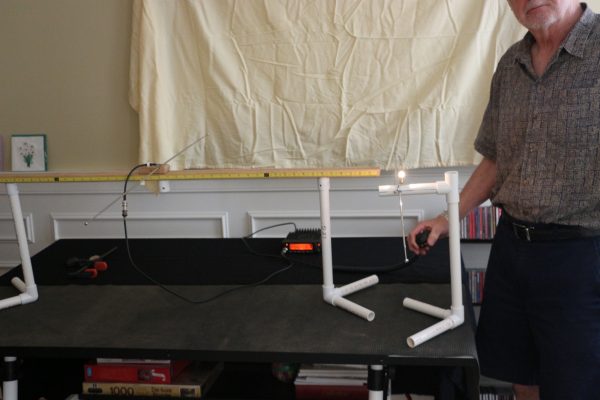

This article discusses some work on designing a matching network to make antennas match well (low VSWR) across the entire ham band. This will be a described in more detail at the September Tech Night.

Antennas have an impedance (or match) that varies with frequency. Transmitters want to see a matched antenna with an impedance of 50 ohms. The antenna has the best match at one frequency and the match gets worse as the operating frequency changes.

Some bands and antennas are more challenging to match than others. Shortened or loaded antennas have a narrow range of match frequencies. The 75/80 meter band has a wide bandwidth in term of percentage.

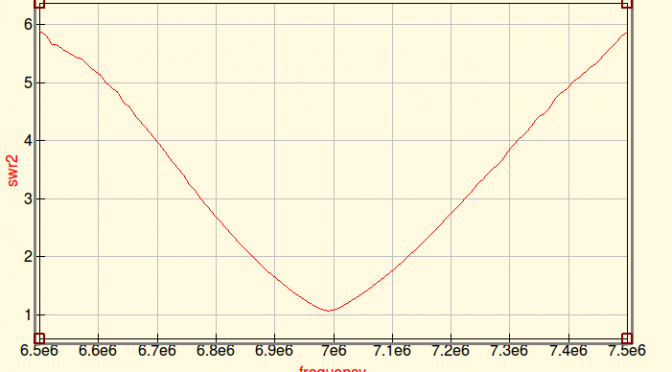

Here’s a plot of the SWR for my 40 Meter Dipole. It’s a good match at 7.000 MHz and degrades to about 2:1 at 7.100 MHz. Obviously, this is not optimized.

Modern radios have built in automatically adaptive matching networks make the radios work over a wider bandwidth, but networks are lossy and reduce transmitted power.

A manual antenna tuner has a lot lower loss than the built in tuner, but it requires manual adjustment. In fact, the extra tuned circuits generally act to make the antenna have even less bandwidth.

The QUCS RF circuit simulation program has the ability to model SWR, bandwidth, matching networks based on data about antenna performance. The antenna data can come from either an antenna modeling program such as 4NEC2 or EZNEC. Or the data can come from a measurement made by a good antenna analyzer.

QUCS also has a built in optimizer. It has the ability to try hundreds of circuit values and home in on an optimal design.

The optimizer setup needs a definition of “optimal”. For the case of a broadband antenna, “The worst case SWR anywhere in the ham band shall be as low as possible”. In the terms that QUCS understands, “minimize the maximum SWR over the frequency range 7.00 to 7.35 MHz.

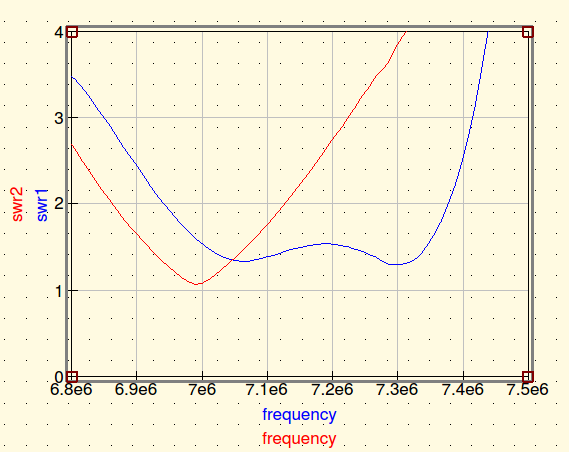

Here is the result from running the optimizer on the data for my mistuned 40M dipole. QUCS has designed a broadband matching network that can achieve less than 1.5:1 SWR over the whole band.

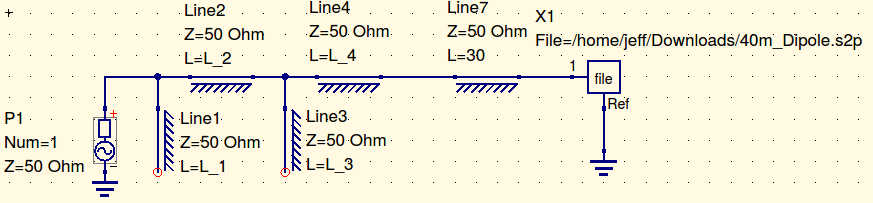

QUCS achieved this by varying the components of a filter network. I drew a general filter network and let QUCS tune the component values. This network is designed with coaxial stubs.

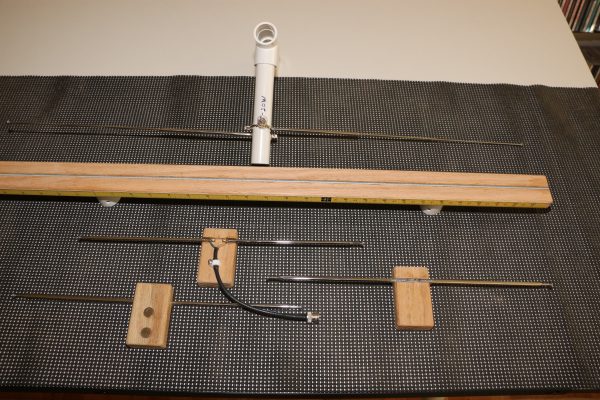

The model of the antenna is stored as a file in the X1 file component. Line7 is a 30-meter coax feedline. The actual matching network consists of Line 1, 2, 3, 4. Each line is 50 Ohm coax. Line 1 and 3 are configured as open stubs. The line lengths predicted by the model are…

- Line 1: 7.75 meters

- LIne 2: 4.47 meters

- Line 3: 8.49 meters

- Line 5: 8.03 meters

Here’s another example. 160-meter antennas are often implemented as shortened loaded verticals. The loading makes the match very narrow-band. The red curve in the plot below shows a top loaded 160 meter vertical. It only covers a fraction of the band.

The blue curve shows the result of an optimization run that selected the values for a 7 component matching network. It achieves about 1.7:1 across the whole band. This network uses capacitors and inductors because coax stubs would be very long on 160 meters.

The component values for this network…

- C1: 3450 pF

- L1: 3.954 uH

- C2: 3978 pF

- L2: 6.951 uH

- C3: 6156 pF

- L3: 2.831 uH

- C4: 4778 pF

I have not built any of these networks to see how they work in practice. The 160-meter network has some extreme values and it is probably very touchy to get right. Building that network to handle Tx power will require vacuum variable capacitors in parallel with high quality stable fixed value capacitors. But, the 160 network doesn’t really need 7 components. Put in one less stage of L-C and the ripple across the passband goes up a bit.

Conclusions

QUCS is a great RF circuit simulator. This shows that it can work with data from an antenna model or analyzer and can optimize matching networks to create a broadband antenna.

Jeff, WA1HCO