Background

The Nashua Area Radio Society (NARS) leadership saw that there may be a lot of latent interest in Parks On The Air (POTA) and portable HF radio operation but club POTA events were not very well attended. Some members had noted that they would like to get involved with POTA but didn’t know how to start. Not knowing about portable operation and not necessarily having the right equipment, folks were reluctant to attend a POTA event. The leadership decided to kick off a “Tiger Team” of interested members in the summer of 2023 to concentrate knowledge in this type of radio operations and share it with all interested members. The team has set the following goals:

- Build and improve the skills needed for successful portable operation

- Share this knowledge in one or more POTA events open to all club members, even those with no equipment of their own and/or no portable operation experience, providing a hands-on opportunity for inexperienced members to learn about and experience POTA operation in a no-stress environment

- Promote continued interest in POTA and SOTA through the next year

A Tiger Team is loosely defined as “a group of experts brought together to solve a specific problem”. A number of members volunteered for this team, with a core group of eight consistently contributing to the effort. Interestingly, while a few of these volunteers had some POTA operating experience, more than half had little or no experience but were very interesting in learning this skill.

Learning

The team started by identifying learning resources, and we found a number of promising sources of information including:

- ARRL Courses

- Getting Started with Parks On The Air

- Getting Started with Summits On The Air (SOTA)

- pota.app and sota.org.uk websites

- NARS Tech Night presentations and Articles

- YouTube instructional videos (search for POTA or SOTA)

- Books

- Portable Operating for Amateur Radio, ARRL

- The Parks on the Air Book, ARRL (new)

There were two areas of learning that we pursued:

Portable Operation

The equipment and operating techniques used for base stations are similar to those required for portable operation, but portable operation comes with its own unique challenges including

- Smaller and more rugged radios

- Low Power (QRP) operation

- Antenna options suitable to each particular location of the activation, as well as the ability to quickly assess the site, erect the appropriate antenna, and tune it for the band(s) being used in the activation.

- Power supplies that are “off the grid”, easy to carry, and with enough capacity to allow operation for the duration of the activation (which could be for a day or several days depending on the trip.)

- Ability to carry in, set up quickly and easily tear down and carry out, in order to maximize the time available for radio operation.

- Being well organized with equipment that is easy to pack and transport.

Parks On The Air Procedures

There are particular procedures for the operation, logging, and reporting in order for operation to be considered a POTA activation. For example, how to identify the particular state or national park or parks being activated using coded designations, what information to exchange over-the-air, and how to report logged contacts.

Practice Outings

Armed with this information, team members then held a number of practice POTA outings at local parks including Miller State Park (K-2662) on Pack Monadnock, Rollins State Park (K-2676) on Kearsarge Mountain (K-4918), and Litchfield State Forest (K-4922), all in New Hampshire. During these outings, the experienced members “Elmer”ed while everyone experimented and learned. The team then identified available equipment and planned the an “Enhanced POTA” club event to take place on October 15th. At this event, all club members were invited to attend regardless of skill levels or equipment owned, and were promised the opportunity to operate just as in the annual Field Day.

Setting for the Enhanced POTA Event

The team chose Winslow State Park (K-2685) in the Kearsarge Mountain State Forest (K4918) for the event. Being at a park within a park made this a “POTA dual activation”. Winslow State Park is situated at 555 meters (1,820 feet) elevation on the northwest slope of Kearsarge Mountain, some 340 meters (1,117 feet) below the summit.

The park has a covered pavilion at the edge of a flat open area, with a number of nice trees nearby for the erection of wire antennas. Conveniently, this area was only a short walk from the parking area, making it easy to carry in equipment.

The day was dry but cloudy and cool with a steady breeze, making for a chilly day of operation. Nevertheless, spirits were high among the twelve members of the Nashua Area Radio Society who participated, along with a number of visitors who stopped by to see what was going on (including a park ranger).

Motivation

Participants shared a number of reasons they found Portable/POTA operation interesting and fun, including:

- Combining love of ham radio with enjoyment of the outdoors

- Meeting the challenges of portable operation, including assembling and organizing gear, practicing antenna setup skills at a variety of sites, and addressing other limitations including portable power and QRP operation.

- Portable operation forces you to work through “the basics” with every activation.

- Enjoying the comradery of other portable operators

- Hams who are not able to set up a home base station are able to operate an HF station

- It’s like a Field Day operation every weekend

Stations

We had a total of five stations operating on five bands (40m, 30m, 20m, 15m, and 10m) using several modes including SSB, CW, and FT8. This provided a nice variety of radios, antenna styles, and power sources for operation during the event.

40 Meters

Ed KA6PNL arrived early in the day while 40m was still an active band. His equipment consisted of an Elecraft KX3 radio operating at 10 watts, a 120 foot End-Fed random wire antenna between a tree limb and the pavilion roof with RG174u feedline, and a Bioenno Power 12V 40Ah LFP Battery (BLF-1240A). He also brought an Elecraft KXPA100 power amplifier that he used solely as an antenna tuner (no amplification). Ed used paper & pencil for logging, and made 14 SSB contacts including one with the POTA representative for Virginia.

30 Meters

Matt WE1H also arrived a bit early and set up his station consisting of a Xiegu X6100 radio at 5 watts using the internal battery as a power source, and a Linked QRPGuys Portable No Tune End Fed Half Wave (EFHW) antenna strung between a nearby tree and the roof of the pavilion with RG58x feedline. Matt operated using CW on 30 meters, and later in the day tried 20m SSB after retuning his antenna for that band. He also used paper and pencil for logging and made 24 contacts, including one that was the first HF contact for a new member of NARS.

20 Meters

Jay KA1PQK set up his station for FT8 digital operation on 20 meters. His equipment consisted of a Yaesu FT-817ND radio operating at 5 watts, a MFJ-2286 Portable Vertical “Big Stick” 17 foot whip antenna with radials mounted on a Home Depot work light tripod, RG8x feedline, a Ryobi 18v Lithion Ion battery with a HomelyLife Voltage Reducer Automatic Buck Boost Converter (DC 8V-40V to 12V 3A 36W) to bring the battery voltage to that required by the radio. Jay used a Dell Rugged Tablet running WSJT-X for FT8 digital operation and also served as a logging tool. A RigExpert Stick Pro Antenna Analyzer was used to tune the antenna. Jay made 24 contacts, with the most distant being in Graham, Washington.

15 Meters

Jack WM0G used the opportunity to operate on the 15m band. His equipment consisted of an Elecraft KX2 at 5 watts with Elecraft MH03 handheld microphone, the internal KX2 tuner and KXBT2 battery, a MP1C Tunable Superantenna with precut radials, and 8 meters (25 feet) of RG8x feedline. For logging Jack used a Samsung Tablet running HamRS docked in a Jelly Comb Model# B046 keyboard (discontinued), with ARRL Logbook Mini as a paper backup.

Jack used the AEA model AA-30 antenna analyzer to tune the vertical antenna, and a Verizon Hotspot for internet access if needed.He also brought but didn’t use Heil BM-17 headphones and a Flashfish 200w solar generator. Jack operated using Upper Sideband SSB on 15 meters, making 5 contacts including four DX contacts to locations as varied as Norwich England, Haldensleben Germany, Dunajská Streda Slovakia, and Muscat, Oman, with the longest distance of 11,020 km (6,848 miles) with 5 watts and a portable vertical antenna!

10 Meters

Mike W1TKO used the day for experimentation and familiarization with some new equipment including a Xiegu X6100 radio at 5 watts and 12v sealed Lead Acid battery and 15 meters (50 feet) of LMR-240 co-ax feedline. One configuration used a Sirio SD27 rigid rotatable dipole tuned for 10 meters on a stout Manfrotto video tripod with the central tube removed to accept the mask of the antenna. Another configuration used a home-brew End Fed Half Wave wire antenna with Pacific Antenna SOTA EFHW tuner on 20 meters, mounted just 3 meters (10 feet) off the ground between a tree limb and the pavilion roof. Mike made just a few SSB contacts, logging with paper and pencil. His most interesting contact was with another POTA operator in Kentucky with his 20 meter configuration.

Challenges Encountered

No portable operating event is without occasional challenges. In fact, this is one of the attractions of this type of amateur radio activity in that no two activations are alike. This section discusses some of the challenges encountered and how they are addressed in this or future activations.

Antenna tuning

Antenna placement and tuning presented some challenges. An antenna analyzer is a critical piece of equipment for the rapid evaluation of the placement of the antenna and tuning of non-resonant antennas such as verticals.

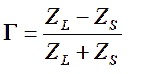

One operator found his vertical antenna to be somewhat sensitive to small changes. To address this, he expanded the frequency range on the antenna analyzer to identify the resonant point of the antenna at its current position, and then adjusting the antenna coil to bring the frequency into the desired operating range.

Near Station Interference

Whenever several stations are operating in close proximity to each other, there is risk of adjacent frequency interference between them. Operators first listened on the intended band of operation and then chose an unused (at this location) band to maximize isolation between stations. One operator tuned across 40m and 20m, and finding them in use decided to operate on 15m with great success.

In addition, radios such as the Yaesu FT-817ND and the Elecrafts have pretty good internal filtering which may have helped reduce interference. One user of the Xiegu X6100, however, experienced significant interference. He felt the radio did not have very robust pre-selector filtering, such that the transmit of another POTA operator on a different band was overloading the receive signal. Distorted transmissions were being picked up from these nearby radios, making it hard to hear distant stations.

Forgotten Items

Operators learned pretty quickly that it is important to have a checklist to ensure that all required equipment is taken to the portable operating site. Also, some members utilize “go boxes” with essential equipment in preassigned places (such as cutouts in foam packing material) to allow quick verification that essential items are packed and ready to go.

Every participant also emphasized the importance of setting up and trying out equipment at or near home before venturing out on a portable operating excursion. Pack and carry out all the equipment intended to bring, and then when the inevitable missing component is found, the remedy is near at hand. This is also important to do if the equipment hasn’t been used in a while to ensure that everything is still operating as expected.

And of course, ensure batteries are fully changed prior to leaving for the activation site.

Equipment Failures

One participant was using gear that was new and this unfamiliarity resulted in several problems. The first symptom was inconsistent fluctuations in receive signal strength and SWR. This was found to be caused by a loose connection within the antenna caused by making connections finger-tight where a tool should have been used, but this alone did not resolve everything. A second issue was found to be an intermittent connection from a cable’s PL259 crimped connector to its coax. Luckily, a spare length of finished coax was at hand, and replacing the cable resolved the issue. Lessons learned include:

- Try out new equipment close to home prior to travel to the operating site

- Bring spares of commonly failing items, such as cables, fuses, etc.

Refinement

As is true for most amateur radio activities, there is always room for improvement. Participants are continually fine-tuning their portable operation equipment and methods. Examples of observations made by participants include:

Packing

For this activation my gear was packed in a couple soft padded travel cases and put in my backpack. I felt like I had too many cases to keep track of. I’ve since moved my gear to Harbor Freight Apache cases. One recent POTA activation I had everything in a medium case, but that took up a lot of room in my backpack (not much room left for layers or food). Currently, I’ve shrunk my setup further to fit into a small Apache case.

Antennas

I’m also in the process of changing my antenna/tripod setup.

- The Home Depot tripod is great, but really too big to carry around in a backpack.

- I’m currently experimenting with a Grabil GRA-ULT01 MK3 lightweight portable tripod. I’m also looking at a smaller antenna – the Gabil GRA-7350TC. I have done some comparisons on 20m between the MFJ 17 ft whip and the GRA-7350TC. The MFJ, being 1/4 wave on 20m, has advantages. The disadvantage is it still doesn’t fit in my backpack when collapsed…. might be time for a different backpack ;-). I still like the idea of a vertical – especially in areas that either don’t have trees, or where you really shouldn’t be throwing things up in trees.

- Also, a vertical antenna generally has a stronger signal and gain at low takeoff angles than a wire antenna mounted too low (less than ½ wavelength) above the ground as a temporary wire antenna is likely to be. DX propagation benefits from a lower takeoff angle.

Extra Items

I plan to include an additional 25 feet of RG-8 coax with a barrel connector, allowing me the flexibility to extend my antenna further from my operating position if needed.

Simplicity

Adhere to the K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple, Stupid) method when selecting your field operation equipment and antenna. I would rather spend more time on the air than troubleshooting rig, power, and antenna problems. Opt for setups that are quick to assemble and less prone to breakage.

In contrast, it’s possible to bring too much equipment on a POTA activation. One participant reported “Since I knew this POTA activation would be close to the car, I purposely went overboard and brought a little red wagon full for gear, tools, and parts. It was a bit comical, but fun. For future outings, I want to streamline the gear I bring. I’d also like to come up with a way to transport my portable setup where I could easily open up a carry case and things would be pretty much set to go, once I raise the antenna.”

Power Supply effect on Transmit Power

It is common to find that the power supply battery type and charge status has an effect on the maximum transmit power provided by the radio to the antenna. For example, both the Xiegu X6100 and the ICOM IC-705 have a max transmit power of 10w when operating from an external battery but only 5w when operating from the internal battery.

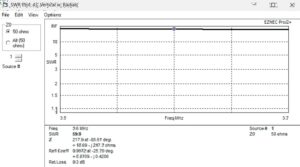

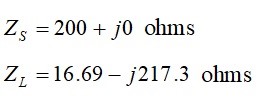

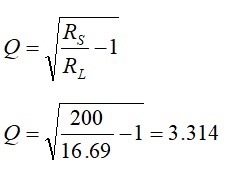

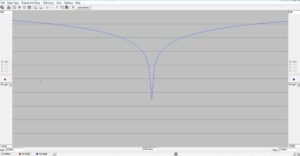

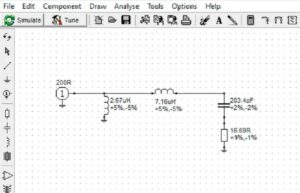

Jay KA1PQK was following up on a commonly held belief that the Yaesu FT-817 may reduce its output power to 2.5W when the input voltage falls below approximately 11V. He originally used the buck/boost converter along with a 3S LiPo battery pack to maintain 12V as the pack’s voltage dropped. From a little bit of internet browsing, he started to question whether or not the FT-817 actually drops its output voltage, or if it just flashes the power indicator as a warning that the voltage is getting low.

The easiest way to find out was to connect the FT-817 to a power meter, dummy load, and adjustable power supply, and test it. He discovered that when the input voltage drops below about 11V, the power indicator starts flashing, but the output power REMAINS AT 5W! He decreased the voltage all the way to 8V (the low limit of the FT-817), and output power remains at 5W all the way.

Experimentation

One participant reports, “I spoke with some visitors who were interested in ham radio. One fellow seemed to have interest in experimenting with and learning about home-brew antennas, very similar to myself. As I am a relatively new ham, I could easily convey how much I’ve learned in the past two years thru NARS activities, by going to local hamfests, reading books & web sites, YouTube, and by hands-on experimenting. I’ve learned ‘don’t be afraid to try.’ A lot of the time I get as much if not more enjoyment from trying to make something work as I do in operating it once (if ever) it’s fully functional.”

Future Portable Operating Events

NARS is hoping to schedule future events at a variety of locales, such as:

-

-

- A park on an ocean beach

- A mix of near-the-car POTA activations and one that’s more of a mild backpack/walk to the activation

- A “Summits on the Air” (SOTA) event requiring a hike to the operating region near a mountain summit. SOTA often requires different equipment that is much lighter and easier to carry a distance in a backpack while hiking to the summit region, and easier to set up in a small space.

-

Conclusion

Portable and POTA activation is an attractive and rewarding amateur radio experience. No two sites are exactly the same, and the ham is continually challenged to address different antenna configurations, operating positions, and power sources.

If you are curious, come to an event and check it out. Even just the process of setting up, operating, and taking down gear will help refine your understanding of the radio operations, how to organize things, of what’s important and what’s not. Even if it’s not your gear, someone will likely appreciate you helping to set up or take down. You can take a turn at operating, and overall it’ll make you a better and more capable operator. It’s just a fun social activity to do it as a group, and spending time with friends in the great outdoors is a plus!